It began innocently enough, as these things often do. Ever since I started baking in earnest several years ago I have been intrigued with Pane di Altamura. Not that I knew exactly what it was, mind you, but the name appeared in many breads that had the golden glow of rich butter in the crumb from the durum wheat. I was able to buy loaves from several local bakers, most notably Acme Bread, to sample. These are good breads! I started experimenting with various formulae and making my own. Il Fornaio, Peter Reinhart’s Bread Baker’s Apprentice, Amy’s Breads, Dan Leader’s Local Bread, Maggie Glezer’s Artisan Bread all had versions and I made and enjoyed each of them. I even shared them with friends, who all left with smiles after eating them. Some of them may have been smiling after drinking that 20 year old Barolo, but they liked the bread, too.

My wife and I spent the last two weeks of October in Southern Italy. Needless to say, we had to make the pilgrimage to the town of Altamura - after all, it was only 15 minutes away from where we stayed in Matera, a city continuously occupied since prehistoric times that’s worthy of a post of its own.

Before we left on the trip I learned about twice milling the durum flour to achieve a flour texture suitable for making breads. Semolina, the coarser grind of durum wheat has sharp edges that tended to cut the gluten network and therefore reduce the ultimate height of the loaf. The double milling is supposed to reduce these spikes. In the U.S. it’s called Extra Fancy or Extra Fine Durum, and in Italy it’s called Rimacinata (re-milled). I've used the Extra Fancy Durum before but I never knew exactly what it meant.

Pane di Altamura is, I believe, the only bread that has a Denominazione d'Origine Protetta, or D.O.P., an E.U. designation that specifies a product and protects the name from being co-opted and used to promote an inferior product. We bought a loaf from a local Paneficio in the city center, and another loaf from a D.O.P. certified bakery on the way out of town. This last loaf was a complete eye (and mouth) opener! It was nothing like any bread I had ever tasted. The loaf had a honey-colored crispy crust that begged to be torn into. The crumb was very yellow, slightly moist and chewy and, at the same time, fluffy and very aerated. There was an ever-so-slight sourness with a rich, a little nutty, earthy flavor. The DOP regulations say (among other things) that the crust must be at least 3 mm thick.

If you are interested in the regs you can download them here (the link doesn’t always work - not sure why)

When we returned home I set out to reproduce the bread as best I could. The quest started by my dragging home a 5 kg bag of the local flour, Semola Rimacinata Grano Duro, in my checked luggage.

Although it wasn’t that expensive there (€8 or roughly $10.50 at the time, less than $8.50 at this weeks exchange rate) for 11 pounds of flour, my supply was obviously very limited, so I wanted to practice on something more available in case the imported version was truly different. I had some Extra Fancy Durum flour from Central Milling (in California) that seemed to be as fine as the Italian version so I decided to use this to develop a bread formula before trying my import.

But where to start? At first I was unsuccessful tracking down any authentic Italian recipes (more about this later), so I took parts from Il Fornaio’s Altamura and Amy’s Breads Golden Italian Semolina for a couple of bakes. These loaves were not worth spending much time on - flat, dense, nearly tasteless, certainly nowhere near the loaf in my minds eye.

On my third attempt working with the Extra Fancy Durum I opted for Leader’s version, which is 72% hydration and 18% pre-fermented flour from an 81%H all durum starter. I several some changes to the formula mostly because the flour seemed unusually thirsty, and ended up with about 77%H dough made with an 86%H starter. Instead of following Leader’s shaping technique, I tried simply to fold the loaf in half trying to achieve that authentic look. This resulting loaf looked OK, but the crumb was very tight. Also, in the photo you can see some unincorporated flour due to the simplistic shaping. And it certainly wasn’t the same color as we had in Italy.

At this point I felt I had to try the flour I brought back to see how it behaved. The first thing I noticed as I prepared the starter was the ease with which the flour hydrated. The flour from Central Milling was very thirsty - building an 80%H starter felt as thick and dry as a 65-70%H whole wheat starter. Using the Grano Duro, the same 80%H more closely resembled an 85-90% WW starter and the flour hydrated as readily as sugar into water. The second major difference is the color. The Grano Duro is a bright yellow compared to the creamy yellow of the CM. Clearly I would have to lower the hydration for this flour. The initial results were unspectacular and disappointing, and it was back to the drawing board.

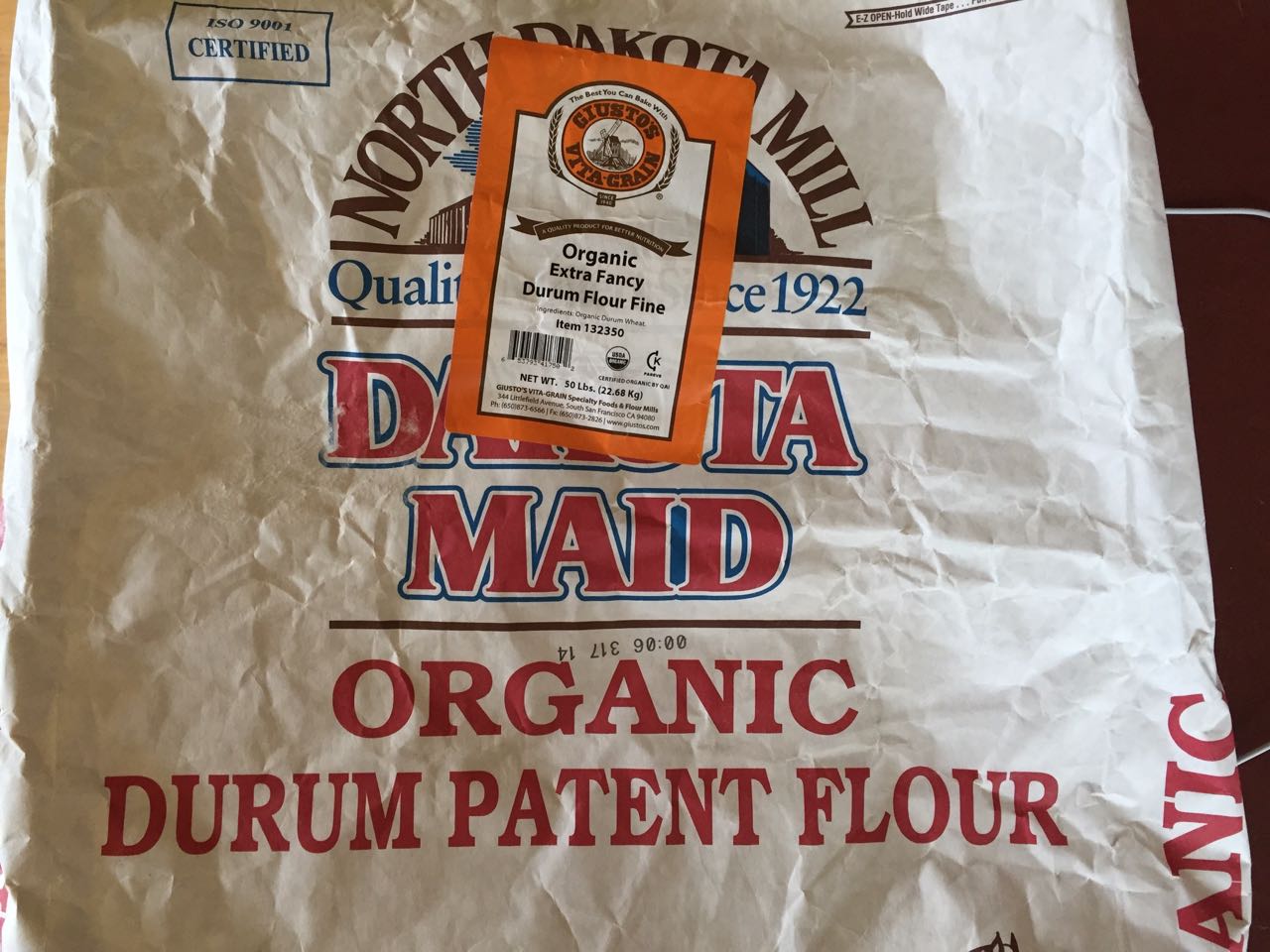

Since the first attempt with Leader’s formula have baked versions of Pane di Altamura a dozen more times. I found another domestic flour from Giusto’s Vita Grain (sourced from North Dakota Mill) that behaved and appeared more like the Grano Duro. Rather than bore you with the details of each and every one, here are some representative photos of the results.

I also found this blog (translated by Google) that gives a pretty detailed formula, although she, too, uses the boule shape. My results are not quite as open a crumb as hers, but pretty close.

My most recent bake was done at a slightly lower hydration. It was a direct comparison between the Italian Grano Duro and the Giusto (North Dakota Mill) Patent durum flour. I was also playing around with long refrigerated overnight bulk ferment rather than retard after shaping, as was the case with loaf shown above.

Comparison between Giusto Flour on the left and Grano Duro from Italy on the right. The respective crumb shots are below.

In the interim and after some intensive web searches I found a few Italian videos that describe the shaping process. Unfortunately I don’t speak Italian, and there is a lot more dialog than action in these clips, but I began to get a sense of how the loaves are shaped.

In this video the various finished shapes are shown in the beginning. You have to wait until around halfway through the video until you see the shaping techniques.

In another video you can advance to around the 10:00 mark to see about 10 seconds of shaping.

At this point, I am fairly happy with the breads when I make basic boules. I think the results are not as good as they could be, and for whatever reason my gluten structure isn’t strong enough to hold up to shaping after long fermentation. Presumably this is why I can’t shape as in the videos. If there are any Italian speakers out there who can translate from the videos I’d be happy for any tidbits that may shed some light on what I am missing. My goal is to be able to shape a loaf like the one at the top of this page.

If you have read this far, thanks for sticking with this long-winded post. My version of Pane di Altamura is still a work in progress. The lack of a wood-fired oven, though, will insure that I never can match the flavor of the original. That’s fine with me - it makes a perfect excuse to go back for more.

-Brad