Pane Valle del Maggia

February 23, 2014

Several bakers on The Fresh Loaf have shown us their bakes of “Pane Maggiore.” This bread comes from the Swiss Canton of Ticino, which is the only Swiss Canton in which Italian is the predominant language.

While the Ticino Canton has Lake Maggiore on its border, the name of the bread supposedly comes from the town of Maggia which is in the Maggia valley, named after the Maggia river which flows through it and enters Lake Maggiore between the towns of Ascona and Locarno.

I was interested in how this bread came to be so popular among food bloggers. As far as I can tell, Franko, dabrownman and others (on TFL) got the formula from Josh/golgi70 (on TFL) who got it from Ploetzblog.de who got it from “Chili und Ciabatta,” the last two being German language blogs. While Petra (of Chili und Ciabatta) knew of this bread from having vacationed in Ticino, she actually got the recipe from a well-known Swedish baking book, Swedish Breads and Pastries, by Jan Hedh.

For your interest, here are some photos from Petra's blog of this bread as she bought it in it's place of origin:

Pane Valle del Maggia. (Photo from the Chili und Ciabatta blog)

Pane Valle del Maggia crumb. (Photo from the Chili und Ciabatta blog)

After this bit of backtracking research, I ended up with four … or is it five? … recipes. I had to decide which one to start with. I decided to start with Josh’s version, posted in Farmers Market Week 6 Pane Maggiore.

Josh’s approach used two levains, one fed with freshly-ground whole wheat flour and the other with white flour plus a touch of rye. I did not grind my own flour but followed his formula and procedures pretty closely otherwise. What I describe below is what I actually did.

Whole Wheat Levain | Wt. (g) | Baker’s % |

Active liquid levain (70% AP; 20% WW; 10% Rye) | 16 | 48 |

Giusto’s Fine Whole Wheat flour | 33 | 100 |

Water | 36 | 109 |

Total | 85 | 257 |

White Flour Levain | Wt. (g) | Baker’s % |

Active liquid levain (70% AP; 20% WW; 10% Rye) | 17 | 50 |

KAF AP flour | 28 | 82 |

BRM Dark Rye flour | 6 | 18 |

Water | 34 | 100 |

Total | 85 | 240 |

Both levains were mixed in the late evening and fermented at room temperature for about 14 hours.

Final Dough | Wt. (g) |

Giusto’s Fine Whole Wheat flour | 137 |

BRM Dark Rye flour | 66 |

KAF Medium Rye flour | 63 |

KAF AP flour | 504 |

Water | 659 |

Salt | 18 |

Both levains | 170 |

Total | 1618 |

Total Dough | Wt. (g) | Baker’s % |

AP flour | 555 | 64 |

Whole Wheat flour | 177 | 20 |

Rye flour | 138 | 16 |

Water | 746 | 86 |

Salt | 18 | 2 |

Total | 1618 | 188 |

Procedures

In the bowl of a stand mixer with the paddle installed, disperse the two levains in 600g of the Final Dough Water.

Add the flours and mix at low speed to a shaggy mass.

Cover and allow to autolyse for 1-3 hours.

Add the salt and mix at low speed to combine.

Switch to the dough hook and mix to medium gluten development.

Add the remaining 59g of water and continue mixing until the dough comes back together.

Transfer to a well-floured board and stretch and fold into a ball.

Place the dough in an oiled bowl and cover.

Bulk ferment for about 4 hours with Stretch and Folds on the board every 40 minutes for 4 times. (Note: This is a rather slack, sticky dough. It gains strength as it ferments and you stretch and fold it, but you still have to flour the board and your hands well to prevent too much of the dough from sticking. Use the bench knife to free the dough when it is sticking to the bench.)

Divide the dough into two equal pieces and pre-shape round.

Cover with a damp towel or plasti-crap and allow to rest for 15-30 minutes.

Shape as tight boules or bâtards and place in floured bannetons, seam-side up.

Put each banneton in a food-safe plastic bag and refrigerate for 8-12 hours.

Pre-heat the oven for 45-60 minutes to 500 dF with a baking stone and steaming apparatus in place.

Take the loaves out of the refrigerator. Place them on a peel. Score them as you wish. (I believe the traditional scoring is 3 parallel cuts across a round loaf.)

Transfer the loaves to the baking stone.

Bake with steam for 13 minutes, then remove your steaming apparatus/vent the oven.

Continue baking for 20-25 minutes. The loaves should be darkly colored with firm crusts. The internal temperature should be at least 205 dF.

Transfer to a cooling rack and cool completely before slicing.

I had some trepidation about baking at 500 dF, but the photos I had seen of the Pane Valle del Maggia were really dark. Also, it made sense that, if I wanted a crunchy crust on a high-hydration bread, I would need to bake hot. I baked the loaves for 33 minutes. They were no darker than my usual lean bread bakes. The internal temperature was over 205 dF. The crust was quite hard, but it did soften some during cooling. In hindsight, I could have either baked the bread for another 5 minutes or left the loaves in the cooling oven for 15-30 minutes to dry out the crust better.

I can tell you, these breads sure smell good!

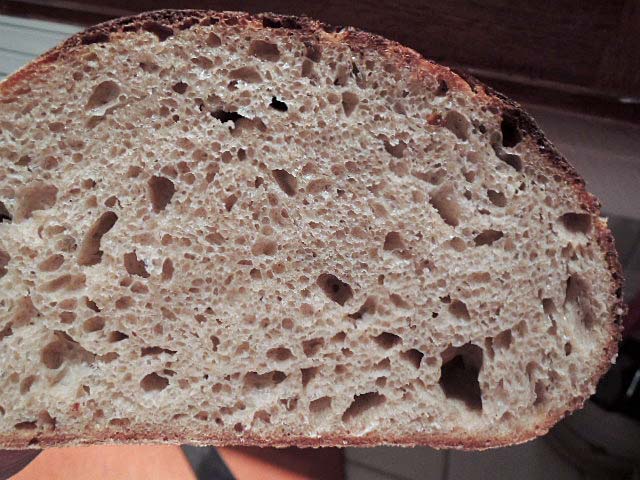

When sliced, the crust was chewy except for the ears which crunched. The crumb was well aerated but without very large holes. Reviewing the various blog postings on this bread, all of the variations have about the same type of crumb. The high hydration level promotes bigger holes, but the high percentage of whole grain flours works against them. In any case, this is a great crumb for sandwiches and for toast.

Now, the flavor: I was struck first by the cool, tender texture as others have mentioned, although there was some nice chew, too. I have been making mostly breads with mixed grains lately, so this one has a lot in common. It has proportionately more rye than any of the others, and I can taste it. The most remarkable taste element was a more prominent flavor of lactic acid than almost any bread I can recall. I really liked the flavor balance a lot! I would describe this bread as "mellow," rather than tangy. The dark crust added the nuttiness I always enjoy. All in all, an exceptionally delicious bread with a mellow, balanced, complex, sophisticated flavor.

Now, it wasn't so sophisticated that I hesitated to sop up the sauce from my wife's Chicken Fricassee with it! It did a commendable job, in fact.

I baked some San Joaquin Soudough baguettes while the Pane Valle del Maggia loaves were cooling.

They had a pretty nice crumb, too.

Happy baking!

David

Submitted to YeastSpotting